Facial recognition systems rely on faces’ analysis to extract a growing number of inferences about an individual’s physiological and psychological characteristics, such as ethnic origin, behaviour, emotions and well-being. These technics are used for a wide array of purposes, among which identification, authentication and emotion detection are the most discussed.

The biometric data uses touch upon some fundamental characteristics of human beings and their pervasiveness has caught the attention of several lawmakers, offering a vast legal patchwork in the US.

The concept of Laboratories of democracy

The concept of legal patchwork derives from the American doctrine regarding “laboratories of democracy”, birthed by Justice Brandeis’ famous dissent for the New State Ice Co v. Liebmann case (1932). He argued that the denial of the right to experiment could have serious consequences to the nation. According to him, “it is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country”.

This approach shaped American States’ autonomy within the federal framework, used as social “laboratories” to create and test laws and policies in a manner similar to the scientific method. This doctrine is rooted in the 10th Amendment of the United States Constitution which provides that “all powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people”.

If a policy achieves successful results, it can be expanded to the national level by acts of Congress. It is also argued that the burden of the legal fragmentation creates a balance of power which could compel industries to cooperate to the law making process, encouraging a more balanced and accountable approach. These policy experiments are increasingly used in the field of technological regulations in the US, to develop open internet laws in the absence of Federal regulation for instance.

This legal fragmentation by design has some merits and may cast an interesting light on the current debates about the use biometric data and Facial Recognition Technologies among American and European lawmakers. It is interesting to view these transatlantic developments as involving two diametrically opposed dynamics, a bottom-up and a top-down regulatory process, both having some merits and drawbacks.

Federal legal instruments

The first attempts to regulate commercial uses of Facial Recognition to uniquely identify or authenticate an individual at the Federal level took the form of non-binding guidelines issued by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 2012 and the Department of Commerce National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in 2016. Neither instrument provided a meaningful definition of biometric information nor Facial Recognition Technologies. These instruments mostly tackled the issues of notice of collection and analysis and consent prior to identification.

On February 12th two Senators announced the introduction of a legislation to protect the privacy of consumers from “rapidly advancing facial recognition technology and data collection practices that heighten the risk of over-surveillance and over-policing”. The Ethical Use of Facial Recognition Act aims to safeguard Americans’ right to privacy by instituting a moratorium halting all federal governmental use of the technology until Congress passes legislation outlining specific uses for the data. This legislation would also prohibit the use of federal funds to be used by state or local governments for investing in or purchasing the technology. Lastly, this Act would create a commission to consider and create recommendations to ensure that any future federal use of facial recognition technology is limited to responsible uses that promote public safety and protect citizens’ privacy. This piece of legislation also incorporates exceptions for law enforcement use of facial recognition pursuant to warrants issued by Courts.

In the meantime, the question of Facial Recognition Technologies for law enforcement purpose is still discussed by US Congress, which expressed its intention to adopt the Facial Recognition Technology Warrant Act (2019-2020) last November. This Act would compel law enforcement services to obtain a warrant based upon probable cause of criminal activity before any use of facial recognition to conduct public surveillance. Some exemptions could be considered for time-sensitive situations. Such warrants could be issued for a maximum period of 30 days and requires law enforcement services to minimize the acquisition, retention and dissemination of information related to individuals not targeted by the scope of the warrant. This act would also provide some oversight to the judges’ decisions, requiring them to report every application’s outcome to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The latter would have to keep a registry and produce reports for the US Senate and the House of Representative.

American States’ legal instruments

In the absence of any Federal initiative to regulate commercial uses of Facial Recognition Technologies, an increasing number of states have been engaged a legislative process to tackle biometric data these past years.

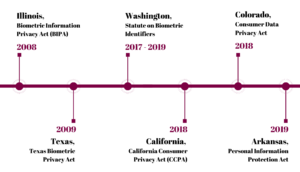

Historically, the State of Illinois and Texas were the first to consider the issue. Several other states followed, including California, Washington, Colorado and Arkansas. In the beginning of this year, the States of Washington and California introduced further Acts aiming to regulate biometric information uses or grant new rights to individuals.

Legislative debates have been initiated on the matter in New York, Florida, Arizona, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin, Maryland, Vermont, Nebraska, Minnesota, Delaware, Alaska, Montana, Oregon among others. This legislative inflation demonstrates the trend among States to enact a clearly framed protection in the matter, although a few bills died in Committee.

Focus on the BIPA and CCPA regime for biometric information

Historically, the first American binding legal instrument was passed in 2008 by the State of Illinois. The BIPA focuses specifically on the uses of biometric information and was inspired by the former EU data protection regime. It requires private entities to establish a written policy, to provide prior notice and collect the written consent of individuals, to ensure a reasonable standard of care to protect such information as well as retention and disclosure restrictions for biometric identifiers.

Most significantly, it is among the few legal instruments at the States’ level which provide a right of action to individual, enabling plaintiffs to recover liquidated damages and attorneys’ fees in whenever a private entity violates the provisions of this Act. In force since 2008, this Act has served as a basis of numerous litigation and case law precising its application. Illinois citizens have already brought several class-action suits based on this Act, against Facebook in 2015, Google in 2016, Snapchat in 2016 and the number of litigations is steadily growing. In the beginning of 2020 new suits were introduced against Motorola and Vigilant Solutions and Clarifai, an AI company which allegedly captured OkCupid profile data to create a “face database”.

In January 2019, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled against Six Flags Corp. and considered that procedural violations, as a failure to properly notify and obtain consent from individuals, constitute harm under the statute. It clarified that these procedural protections are crucial given that biometric identifiers cannot be changed if compromised and noting that the private right of action is the only enforcement mechanism available. It ruled that “the violation, in itself, is sufficient to support the individual’s or customer’s statutory cause of action” even without a demonstration of an actual injury or harm by the plaintiff. This ruling is a very strict precedent and it is argued that it has left few defences actionable by the defendant.

Nonetheless, federal courts’ caselaw is more demanding and require the plaintiff to allege an injury-in-fact sufficient to establish standing to proceed in federal court, as required by the Article III of the US Constitution. Hence, an injury-in-fact must be concrete and particularized as well as actual and imminent, thereby excluding conjectural or hypothetical harms. The judges therefore considered that a bare procedural violation devoid of any concrete harm cannot qualify as an injury in fact to establish standing. This position opened a defence in BIPA lawsuits, under certain conditions, as detailed in the Heard v. Becton, Dickinson & Co and the Hunter v. Automated Health Systems cases. Federal courts may be competent if they have a basis for exercising subject-matter jurisdiction over the action. This is the case when there is a diversity of citizenship of the parties, where plaintiff’s action involves a claim under federal law or under the Class Action Fairness Act. When a civil action is filed with a state court, the defendant may remove the action to federal court by filing a notice of removal. If the district court determines that it lacks subject matter jurisdiction at any time before entry of final judgment, the district court must remand the action to the state court.

Ten years later, the State of California adopted the CCPA which grants consumers several actionable rights. As we explained in a previous article, this legislation entered into force last January, but the Attorney General’s powers to prosecute are suspended until July 2020. The class actions filed and caselaw development ought to be closely scrutinized.

[table id=3 /]

As far as law enforcement is concerned, some local decisions implemented a temporary ban of facial recognition technology. San Francisco was the first city in the US to ban the use of the technology by city agencies, including the police department, in May 2019. It was rapidly followed by Somerville and Oakland in June and July 2019. Other cities, such as New York City, are currently considering or voting such bills.

Moreover, the State of California was the first to enact a 3-year moratorium on the use of facial recognition technology in police body cameras, taking effect in January 2020.

Mathias Avocats will keep you informed of the evolution of these regulatory developments.